Who were the Founding Fathers? What makes someone a Founding Father? They were key political leaders during the Founding Period of the United States. The Founding Period includes the run up to the American Revolutionary War, the war itself, and the postwar period through the Constitutional Convention and the ratification of the Constitution.

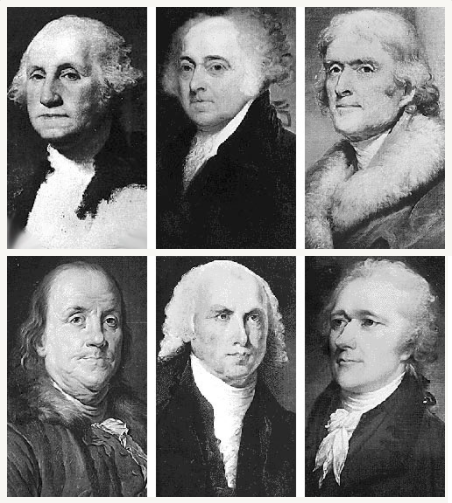

Who were the Founding Fathers? Any list of Founding Fathers may be controversial. Different people or scholars will include different people on a list. We consulted various lists to make sure our selections were not too far afield. While many others deserve consideration, we identified a core of seven: George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and Benjamin Franklin. Due to space constraints here, we present very brief introductions to the lives and careers of the first three. We will present similar introductions to the others in the future, and likely branch out beyond the core seven as well. Each of these men deserves an article of his own, but we seek here to introduce a few at a time to the interested reader.

George Washington: The Father of Our Country

The first of the Founding Fathers we will consider is George Washington. George Washington was born February 22, 1732, in Popes Creek Plantation, Virginia. His family there ran a tobacco plantation since settling the area in 1657. Washington’s father, Augustine, was a justice of the peace and built the plantation home only a few years before Washington was born. His mother, Mary, married Augustine in 1731.

Early Years

Augustine died when George was only 11 years old, leading George to inherit Ferry Farm and ten slaves. This was the first of several times throughout his life that he would inherit slaves. His attitude toward slavery would gradually shift, however, until by 1783, he privately sympathized with a plan by Marquis de Lafayette to abolish slavery, even (unsuccessfully) attempting to implement the plan in the last few years of his life to transition his slaves to free tenant farmers. To avoid breaking up families, Washington refused to sell slaves, leading to a significant expense to provide for their care and upkeep. In his will, he ordered all slaves to which he had title to be freed upon the death of his wife. In 1752, George’s brother, Lawrence, died, and George inherited his estate, Mount Vernon near Alexandria, Virginia.

Military and Political Career

In December 1752, Washington began his military career in service to Great Britain. He was appointed commander of the militia in Virginia and served in the French and Indian Wars. In January 1759, George married the widow Martha Custis, and became a father to her two children. He resigned his commission, returning to Mount Vernon in about 1759. Once back there, he served in the Virginia House of Burgesses (the legislative body for the colony) until 1774.

In 1774, Washington served as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In October 1775, six months after the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress appointed Washington Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. This began an extended period of service to the revolutionary cause. In 1781, British General Cornwalis surrendered at Yorktown, the last major battle of the Revolutionary War. In 1783, the Treaty of Paris formally ended the Revolutionary War. Washington resigned his military commission that same year.

Service in the Constitutional Period

In May 1787, what we now know as the Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia. They concluded their work in September of that year, submitting the Constitution to the states for ratification. George Washington was elected president of the convention. Washington was elected the first President of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797.

Washington died from a throat infection in December 1799.

John Adams: The Principled Firebrand

In popular awareness today, John Adams is likely the least recognized of the three FOunding Fathers we discuss here. Adams was born on October 10, 1735 in Braintree, Massachusetts on the family farm. His parents were John Adams Sr. and Susanna Boylston. John Sr was a Deacon in the local Congregational Church and farmer. He could trace his family back to 1638 when Henry Adams immigrated from England. Susanna Boylston was from an established medical family.

Early Life and Career

Adams attended Harvard College, beginning in 1751 at the age of 16. During his time at Harvard, Adams was drawn to the classics, reading the classical texts in the original Greek and Latin. In 1755, Adams graduated with an AB from Harvard. With the outbreak of the French and Indian Wars, he lamented being on track for a legal, instead of military, career. In 1756, he began studying law and earned an AM from Harvard in 1758. A year later, he was admitted to the bar.

In 1759, John met fifteen-year-old Abigail Smith. They married five years later on October 25, 1764. The couple had six children, most notable of which was John Quincy Adams, who served as the sixth President of the United States. Adams practiced law in Massachusetts, and was a major advocate of the right to counsel for those accused in criminal proceedings. So important was this principle of the right to counsel that Adams acted as defense counsel for the British soldiers charged for their part in the Boston Massacre in 1770.

Resistance to British Rule

Adams took a legalistic approach to resisting British rule. He questioned Parliament’s authority to tax the colonies. As early as 1763, he began publishing essays under pen names outlining why resistance, and ultimately independence, was necessary. While perhaps harboring private doubts about his own capabilities, he had unshaken faith in the cause of American Independence. He was an insatiable firebrand in arguing for independence.

Political Career Before and After Constitution

Adams served as a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses. He also served as a judge and took various diplomatic posts in England and the Netherlands. After ratification of the Constitution, Adams served as the first Vice President of the United States, under George Washington. He then succeeded Washington, becoming the second President of the United States. Political parties began to take shape about this time, with Federalists in the government and Republicans in the opposition. In this context, Adams was a Federalist.

Death

John Adams died July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Adams and Thomas Jefferson had developed an intense (and frequently personal) rivalry. A reconciliation took place in about 1812, and the two Founding Fathers began an extensive correspondence that continued until their deaths. Adams’ last recorded words were, “Jefferson still lives.”

Thomas Jefferson: Father of the Declaration of Independence

Thomas Jefferson was born April 13, 1743 at his family’s Shadwell Plantation in Albermarle County, Virginia. His parents were Peter Jefferson, a planter, and Jane Randolph. In 1757, Peter Jefferson died, and Thomas Jefferson (at age 14) inherited thousands of acres of land, including what would become the famous Monticello estate.

Early Life

Jefferson studied Latin and Greek with a local schoolmaster following his father’s death. In 1760, he entered the College of William and Mary. He was a committed student, and began studying law in 1762. In 1767, Jefferson began his own law practice and gradually gained a reputation as an imposing legal scholar. In 1772, he married the widow Martha Skelton and settled at Monticello, then still under construction since being started in 1768. Tragically, Martha died 10 years later.

Pre-Declaration Political Career

In 1768, Jefferson ran for and was elected a delegate in the Virginia House of Burgesses. He entered politics just as opposition was solidifying against British taxation in the colonies. Jefferson quickly became an early and strong advocate for independence, writing A Summary View of the Rights of British America in 1774. Jefferson was sent as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in June 1775.

In June 1776, Jefferson was appointed to a committee that also included John Adams and Ben Franklin to draft a formal document outlining the reasons for the colonies to break away from Great Britain. Jefferson drew heavily on his previous writings to craft a first draft of the Declaration of Independence. The first draft of the Declaration included an indictment of the slave trade, but that language was removed to keep South Carolina’s and Georgia’s support for the document.

Jefferson and Slavery

Like George Washington, a fellow slave owner, Jefferson was internally conflicted on the issue of slavery. He regarded the practice as antiquated and wrote about how it would harm blacks and whites alike. He saw problems with sudden emancipation, however, and believed a gradual emancipation was both desirable and inevitable. His aversion to public conflict and the controversy his early writings on slavery had produced led him to withdraw from the public debate on slavery in his later years.

It is almost certain that Jefferson had a relationship with the slave Sally Heming. It is suggested by some that they were secretly married at some point. Married or not, they are believed to have had several children. Sally and at least some of the children and other slaves traveled at times with Jefferson to foreign countries, such as France, where they could be free if they chose to run away. None of the slaves did, suggesting that there may have been some truth to Jefferson’s portrayal of himself as a benevolent master who cared for his “family,” as he referred to everyone (slaves included) at Monticello. While several of his children with Sally Hemming were freed as they approached adulthood, many of the remaining slaves were mortgaged (like much of the estate) and therefore not really his to free.

Colonial Political Career After Declaration of Independence

In September 1776, Jefferson was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates. While serving there, he worked on establishing a new constitution for the state and reforming its legal code. In 1779 and 1780, Jefferson was twice elected to one-year terms as Governor of Virginia. In 1783, the United States was governed as a confederation, and Jefferson was appointed as a delegate to the Confederation Congress. Though ultimately rejected by Congress, Jefferson wrote a law which would have banned slavery in new territories. Such a ban was imposed in 1787 for the Northwest Territories (present day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota) in the Northwest Ordinance.

In 1784, Jefferson was sent to France on a diplomatic mission in Europe. He returned to the United States in 1789.

Political Career in Constitutional Period

Jefferson accepted an invitation to serve as Secretary of State under President Washington. While Washington was largely above party politics, Jefferson was instrumental in beginning to form the Republican Party. This early political party advocated for local control and limiting centralized power. Decades later, this party would splint into two main factions, the Democratic-Republican Party, and the National Republican Party. While the National Republican Party withered away, the Democratic-Republican Party was the forerunner of today’s Democratic Party. Today’s Republican Party was organized much later, in the 1850s.

Previously friends, the development of opposing political parties made Jefferson (a Republican) and Adams (a Federalist) rivals by the election of 1796. In that election, they ran against each other to follow Washington into the White House. Adams won that election, but because of the structure of the Electoral College at the time, Adams served as a Federalist President with Jefferson as a Republican Vice President, the second Vice President of the United States.

The hostility between these men grew through the 1790s and early 1800s. The election of 1800 was a bitter rematch of the 1796 election with Jefferson winning this time. This became the first time that a transfer of power from one political party to another would happen under the United States Constitution. It could have gone very poorly, but the transfer of power from a Federalist administration to a Republican administration proceeded peacefully. Jefferson was the third President of the United States, serving for two terms. Following his service as President, Jefferson founded the University of Virginia in 1819.

Late Years and Death

Jefferson was mired in debt in his later years, and upon his death much of his property (including slaves) was auctioned off to pay creditors. Jefferson’s health deteriorated in 1826, and he became bedridden in June of that year. Jefferson viewed the Declaration of Independence as his greatest achievement. On either the evening of July 3 or morning of July 4, 1826, Jefferson spoke his last words, “Is it the Fourth?” At his death on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, John Adams had proclaimed that “Jefferson still lives,” not aware that his longtime colleague, rival, reconciled friend, and fellow Founding Father had died earlier that day.

Final Thoughts on the Founding Fathers

As we can see from these brief introductions of just these three men, the Founding Fathers, like most people in the past or present, were not one-dimensional people. Their positions on a variety of issues, such as the structure of government, racism, or slavery, often defy simple description.

The Founding Fathers deserve respect and admiration for what they did accomplish in laying the foundation for this nation. They, however, were men – fallible and bound by a world view of the time that they lived. They did not necessarily get everything right. On the question of slavery, we would fight a bloody civil war to settle the issue – something even abolitionists of the founding period wanted to avoid.

In 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King declared that he had a dream that “one day this nation will rise up and live up to its creed.” Without the likes of Washington, Adams, and Jefferson, there would have been no American creed for a Martin Luther King to appeal to.