One of the least understood things about American government is how we select a president. Many people don’t understand it. Many people think it should be changed. In this article, we will explain how it works, and in a later article, we will discuss what the advantages are to having the electoral college.

The Twelfth Amendment modified how the electoral college works. The original form of the electoral college would seem even more bizarre to today’s observer. We will consider how it works in its current form. Let’s dig in.

Electors: Who do we really vote for?

Many people would be surprised to learn who you really vote for in a presidential election. When you vote for president, you are really voting for a slate (or group) of electors who will vote for the president. The Electoral College is that group of electors.

What is an elector? In this case, someone who will go on to cast an actual vote for president. Each candidate for president will have a slate of electors in each state. For example, in the 2020 presidential race, in each state, Joe Biden had a group of people pledged to vote for him running as electors. Donald Trump had a group pledged to him. The minor candidates had their own slates of electors as well.

Where do these electors come from? The electors tend to be very loyal members of the respective political parties. They may hold offices in the party. Since the presidential electors will actually vote for the president in December, it is important to actually have people who will vote as expected. We will discuss this point a bit more later.

How many Electors are in the Electoral College?

How many electors does each state get? The Constitution says that each state gets a number of electors equal to the total number of representatives and senators from that state.

Every state has two senators. The number of representatives each state gets depends on its population. Let’s say you live in a state that has three representatives in the House of Representatives. Your state would elect five presidential electors.

Each state has at least one representative in the House of Representatives. Each state, then, gets to select, at least three presidential electors. In 2024, six states will have the minimum of three electors. At the other extreme, California will select 54 electors in the 2024 election.

In addition, the Twenty-Third Amendment allows the District of Columbia (D.C.) to select presidential electors. D.C. gets as many electors as it would if it were a state. It may not have more electors than the state with the smallest population, though. Currently, D.C. can select 3 presidential electors.

There are 435 members of the House of Representatives and 100 members of the U. S. Senate currently. That means the states select 535 electors. Add the three from the District of Columbia, and there are 538 electors in total.

If a new state were to be admitted to the Union, that state would get two senators. Members of the House of Representatives would be reapportioned, but there would still be 435. The number in the Electoral College would rise to 540.

If Congress changes the number of representatives in the House of Representatives, the size of the Electoral College will change. The number of representatives in the House of Representatives has been set at 435 since 1913.

How are the Electors chosen in an election?

The Constitution provides very broad discretion each state about how to select electors. The Constitution provides that the electors shall be selected “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct.” In other words, the states can theoretically do whatever they want to select presidential electors. The state legislatures could even select the electors themselves. In practice, though, all of the states currently use a popular election to select presidential electors.

Winner-takes-all rules

In forty-eight states and in the District of Columbia, the presidential candidate that gets the most popular votes gets all of his or her electors elected. It doesn’t matter if the candidate wins by one vote or a million votes. These are “winner-takes-all” rules.

If Joe Candidate gets the most popular votes, all five of Joe’s electors will be elected. It doesn’t matter if the election is close or a landslide. If there are three or more strong candidates in the race in the state, Joe Candidate might win all of the electoral votes with a minority of the votes. Imagine a three-way race in which Joe Candidate got 5,000 votes, Sam Statesman gets 3,000 votes, and Nancy Newcomer gets 4,000 votes. Joe Candidate gets all the electors even though 7,000 people voted against him, as opposed to 5,000 voting for him.

Selection of Electors by Congressional District

In most states, one party or the other dominates if you look at the state as a whole. If you look inside the state, though, there are often some areas that are Democratic strongholds and some that are Republican strongholds. Because of this, many states have both Democratic and Republican members of Congress.

To account for these variations within a state, another method of selecting electors exists. This process allows for some Republican electors and some Democratic electors to be sent from the same state. Let’s look at how this alternate selection method works.

In two states, Nebraska and Maine, the rules are not winner-takes-all. Instead, electors are selected by congressional district.

Nebraska, for example, has three representatives sent to the House of Representatives in Congress, so it gets five electors. In Nebraska, the votes for president are tallied for each congressional district. The winner in each congressional district wins one elector for that district. It is winner-takes-all within the congressional district, but not for the state as a whole. That selects three of the electors.

What about Nebraska’s other two electors? The overall winner of the vote in Nebraska wins two at-large (or statewide) electors. To sum up, in essence, an elector is selected in each congressional district, plus a “bonus” two electors for the person with the most votes in the state as a whole. Maine’s system is similar.

The Electoral College Meets, Sort of

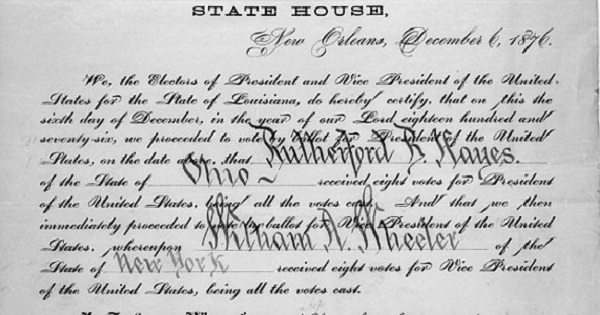

On the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December (this date is set by law, not by the Constitution), the electors meet in their respective state capitols and cast their ballots. Each elector votes for one candidate for president and one candidate for vice president. Presumably, the electors vote for a presidential candidate and that candidate’s selection for vice president. The ballots are then sealed and sent to the President of the Senate.

The President of the Senate (the Vice President of the United States) must then open the ballots on January 6 (a date set by statute, not by the Constitution) in the presence of the members of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The ballots are then counted.

Twenty-six states have laws that require electors to vote for who they are pledged to. There is no Constitutional or federal law requirement that they do so. Nonetheless, it is rare for them to vote any other way. An elector who does not vote as expected is an “unfaithful elector.”

If someone wins a majority (270 or more) of the votes for president, that person is elected president. If someone wins a majority (270 or more) of the ballots cast for Vice President, that person is elected Vice President. The new President and Vice President are sworn in and their terms begin at noon on January 20. This is usually where the process ends.

Coming up, though, we will discuss what happens if no candidate for president or vice-president wins a majority. Though rare, this has happened. Things can get pretty messy when it does, and discussing that scenario deserves its own article.