The Constitutional Convention began on May 25, 1787. The outcome of the convention was the current Constitution of the United States. We will explore some of the major factors leading to calling the Constitutional Convention.

In 1787, many problems were evident in the United States government under the Articles of Confederation. These problems built up until it was clear that some significant changes needed to be made.

Before the Constitution: Articles of Confederation

On November 15, 1777, the Continental Congress approved the Articles of Confederation. At the time the Continental Congress was considering independence in 1776, they also created a committee to consider how the former colonies would work together. This committee included one delegate from each colony.

Under the leadership of John Dickinson from Delaware, the committee drafted what we now know as the Articles of Confederation. The Articles of Confederation really acted as the first constitution of the United States. Let’s look briefly at that document. Though the Articles had been approved by Congress, they still needed to be ratified by the states. This was completed on February 2, 1781, at which time the Articles went into effect. They remained in effect until ratification of the current Constitution in 1789.

One thing we should note is that the Articles of Confederation were adopted by delegates to the Continental Congress. At the time, the word ‘congress’ had a different meaning than it does now. Today, we think of a congress as a national legislative body. At the time, though, it referred to an international gathering of delegates or representatives from different countries. This is important to keep in mind, since the attitude at the time was that the states formed by independence were independent not just from Britain, but from each other. In January, 1776, Thomas Paine published his famous pamphlet, Common Sense, which sought development of an national American identity, but it would take many years for such an identity to form.

Confederation with Very Limited Power

The Articles named the confederation, “The United States of America,” but it was an alliance among independent states. Article III describes it as

a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defence, the security of their Liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretence whatever.

We will touch on a few highlights of the confederation created by the Articles. In this confederation, people were free to travel between states. Article IV provided for extradition of criminals and “full faith and credit” by the states in other states records and proceedings.

Each state could appoint between two and seven delegates to represent the state in Congress. Each state, however, was given one vote in Congress, regardless of how many delegates they sent.

Congress had the power to conduct foreign policy on behalf of the United States. This included the power to make treaties which the states were obligated to respect. Along with foreign policy, Congress had the authority to set military policy. Though the states would help to raise an army, the costs of military forces for the common defense were charged to the Congress.

Congress was empowered to settle certain disputes among the states, regulate the money of the United States (but states could also print their own money), and set standard weights and measures. Congress could appoint officers of the United States. They could also borrow money.

The Articles provided for a “Committee of the States” which could exercise certain powers, even when Congress was in recess. This committee consisted of one delegate from each state.

Weaknesses of Articles

The Articles of Confederation had several structural weaknesses. These weaknesses made it unrealistic for the government under the Articles to function as a national government.

No Judiciary or Executive

Notable in this discussion of the Articles of Confederation is the absence of a judicial system or an executive branch of government. While the Congress could appoint civil officers of the government, there was no unified executive structure. Likewise, there was no judicial structure specified other than what Congress might create. Most importantly, though, the lack of a coherent executive authority and reliance on executive action by committee, made it difficult for the government to respond.

No taxing power

Congress was responsible for a lot of things. These things cost a lot of money. Consider that Congress was charged with paying for an army and navy. In 1777, when the Articles were approved, Congress was in the midst of managing the Revolutionary War – an extremely costly affair. Congress, however, had no taxing power. They could ask states for financial contributions, but states often did not comply fully with these requests.

No Power to Regulate Interstate Commerce

Congress also had no power to regulate interstate or foreign commerce. States could do what they wanted as far as regulating commerce with other states or countries. This led to trade disputes among the states.

Amendments to the Articles required unanimous consent from the states. In addition, many Congressional actions required a super-majority of nine of the thirteen states to agree. This made legislative action action particularly difficult.

Today, we look at these as weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. At the time, however, these were initially seen as a virtue. Remember that the states viewed themselves as independent. The Articles of Confederation were created by the states. Concerned about abuses of centralized power, the states jealously guarded their own power. When the Articles were written, there was no desire to risk creating our own monarchy or oppressive government here, at the very time we were trying to get rid of an oppressive remote government in Britain.

Shay’s Rebellion

Funding for military pay was often inadequate. Indeed, during the war, George Washington wrote many letters to the Continental Congress complaining about the lack of funds for pay and supplies. This lack of resources was often due to states not contributing their assigned resources to the Congress.

Many of the soldiers in the Continental Army were farmers in their civilian lives. When those living in rural Massachusetts returned home, many found themselves in dire financial circumstances. To compound this, British merchants supplying merchants in American towns began to demand payment in hard currency after the Revolutionary War. Credit was no longer extended.

The merchants, forced to pay hard currency to their suppliers, demanded hard currency from their customers. These customers included the farmers in rural Massachusetts. This was coupled with taxes in Massachusetts which exceeded what was being paid under British rule. The farmers were unable to repay their debts. Many lost their farms to foreclosure.

Appeals to the Massachusetts government for help to relieve pressures on the farmers were largely ignored. Pressure continued to build through 1786. Farmers began to organize themselves similar to the Committees of Correspondence that had organized resistance to British rule throughout the colonies.

The insurgent movement, called Shaysites by some in the press, promoted the involvement of Revolutionary War veteran Captain Daniel Shays. It is a matter of historical dispute whether Shays was deeply involved in the movement, or just a member of the movement whose name would lead credibility to the effort.

Shutting down the Courts

In August 1786, after the legislature adjourned without taking action to help the farmers, the movement turned to direct action. In an effort to block bankruptcies and foreclosures, the insurgents began to block access to state courts. If the courts could not function, they could not take action against the indebted farmers.

In September, Governor James Bowdoin denounced the actions and began making plans for a response. Three days later, the militia refused to defend the court in Worcester against insurgent action. Disruption of the operation of the courts began to spread throughout much of Massachusetts. When courts could meet, they required protection from the local militias.

Congress did not have the funding to commit troops to restore order in Massachusetts. Ultimately, Governor Bowdoin organized a privately funded militia. This militia was led by Continental Army General Benjamin Lincoln. By early February, 1787, Lincoln’s march convinced most of the insurgents to disband. The uprising was essentially over.

Shay’s Rebellion was the first major challenge to the fledgling American nation. At the time, there was concern that the rebellion could have spread to neighboring states. The confederation government had proved itself unable to maintain peace.

Annapolis Convention Calls for Constitutional Convention

Disputes between Maryland and Virginia arose in 1785 over use of the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. Discussions surrounding that issue led to broader conversations about interstate commerce within the United States. Virginia eventually passed a resolution calling for a convention in Annapolis, Maryland, to be held on September 11, 1786.

This convention was to consider changes to the Articles of Confederation related to interstate commerce. It was not supposed to be a Constitutional Convention to create a new charter for government. It turned out to be a step down that road.

The convention did take place, running from September 11 to September 14, at Mann’s Tavern in Annapolis. Most of the states appointed commissioners to represent them at the convention. Only twelve commissioners actually arrived for the convention.

These twelve represented only five states (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Virginia). Four other states appointed representatives who did not show up. The remaining four took no action at all.

New Jersey empowered its commissioners to go beyond just considering defects in the Articles concerning interstate commerce. Other commissioners were limited to discussing interstate commerce.

Given the poor attendance, there was really nothing the convention could do. The report from the convention included the following.

That there are important defects in the system of the Federal Government is acknowledged by the Acts of all those States, which have concurred in the present Meeting; That the defects, upon a closer examination, may be found greater and more numerous, than even these acts imply, is at least so far probably, from the embarrassments which characterize the present State of our national affairs, foreign and domestic, as may reasonably be supposed to merit a deliberate and candid discussion, in some mode, which will unite the Sentiments and Councils of all the States. In the choice of the mode, your Commissioners are of opinion, that a Convention of Deputies from the different States, for the special and sole purpose of entering into this investigation, and digesting a plan for supplying such defects as may be discovered to exist, will be entitled to a preference from considerations, which will occur without being particularized.

The delegates thus called for a new convention to be held to broadly discuss all of the “greater and more numerous” defects in the government leading to “the embarrassments which characterize the present State of our national affairs, foreign and domestic.” This led directly to the Constitutional Convention.

Constitutional Convention

On February 21, 1787, the Continental Congress approved a resolution for another convention “for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation.” The convention was set to begin on May 14, 1787, but only Virginia and Pennsylvania delegations arrived on time. Opening business was delayed until May 25, 1787, when a quorum of seven states was present.

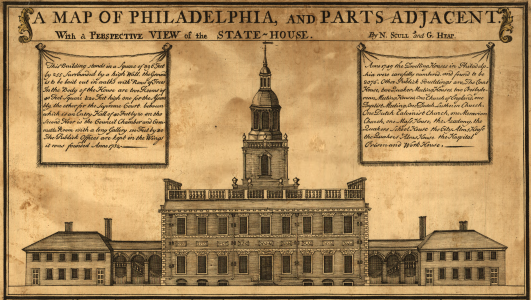

The convention was held in the Pennsylvania State House. This was the same location where the Declaration of Independence was debated and ultimately adopted by the Continental Congress. In September of 1787, the Constitutional Convention completed its work, having drafted the current Constitution of the United States.